Inversion of Control

Introduction

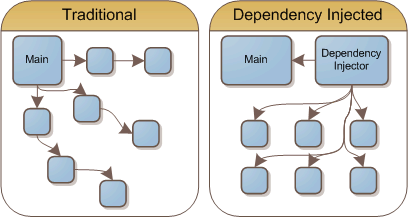

Inversion of Control (IoC) is a design principle in which custom-written portions of a computer program receive the flow of control from a generic framework. A software architecture with this design inverts control as compared to traditional procedural programming: in traditional programming, the custom code that expresses the purpose of the program calls into reusable libraries to take care of generic tasks, but with inversion of control, it is the framework that calls into the custom, or task-specific, code.

Inversion of Control conforms to the Hollywood Principle ("Don't call us. We'll call you."). In this case, and object doesn't call for its own dependencies; it recieves its dependencies at creation from some Dependency Injector object.

Reflection

In programming, Reflection is simply the code having a look at itself (or introspection). With Reflection you can examine objects at runtime to determine what properties, methods, and field values that they have. Generally speaking it's bad practice to architect using reflection. Still, in order to understand IoC, you need to understand that Reflection is possible. It's also what makes tools like JetBrains dotPeek and decompilers possible.

Inversion of Control uses Reflection to "Magically" construct classes. All IoC frameworks have something equivalent to a Container, which can be thought of as a Magic Hat. The IoC container uses reflection to examine the constructors (and sometimes properties) of a class to determine whether or not it can populate that constructor with something else that it has in it's Container.

Dependency Lifetime

All IoC containers have a concept of lifetime and some flavor of the following:

- Per Scope/Per Request: In web frameworks, this initializes a new instance of the object on every request.

- Transient: This initializes a new instance of the object for each constructor/property.

- Singleton: This uses the same object to resolve for all constructors/properties.

Example

We'll use C# for our examples. One of the containers available in .NET is called Unity.

Dependency Registration

Here's an example of registering a type with Unity:

IUnityContainer myContainer = new UnityContainer();

myContainer.RegisterType<IProductRepository, ProductRepository>();

var myServiceInstance = myContainer.Resolve<IProductRepository>();

This means that we are truly swappable with one line of code where we initialize our IoC Container.

Constructor Dependency Injection

Now, the IProductRepository interface is linked with the ProductRepository class. So, later in our code when we need to use an instance of IProductRepository, we can set up like this with constructor dependency injection:

public class HomeController {

private IProductRepository _productRepository;

public HomeController(IProductRepository productRepository){

_productRepository = productRepository;

}

}

Now we have no need to create an instance of IProductRepository. Unity will pass in the correct instance when HomeController is created.

Property Attribute Dependency Injection

However, we can make this even simpler with property attribute dependency injection:

public class HomeController {

[Dependency]

public IProductRepository ProductRepository { get; set; }

}

The benefit here over the constructor is that you don't have to have a Mega Constructor when there are lots of dependencies. The downside is that for other uses where the class truly requires it, then it's not guaranteed after construction. That's why this is best reserved solely for Controllers.